Para os países que falam Inglês

A Jagunço captured

by soldiers of the Brazilian army. This and other warriors who defended

Canudos, after being captured were summarily executed by beheading. Photo of

Flávio de Barros – http://www.scielo.br

The troops

tried to reinforce the encirclement penetrating step by step into the interior

of the village, but they met with a fierce resistance that thwarted their

advance. Furthermore, the jagunços fell back, but did not run away.

They remained nearby, a few steps away, in the next room of the same house,

separated from their enemies by a few centimeters of pressed earth. There

wasn’t much space in the village. This caused those who wanted to preserve

themselves and who put up an increasing resistance to the soldiers by crowding

them to gather in the hovels. Though they gave up on some things, they reserved

quite different surprises for the victors. The cunning of the sertanejo made

itself felt. Even in their most tragic moment, they would never accept defeat.

Far from being satisfied with resisting to the death, they would challenge the

enemy by taking the offensive.

On the night

of September 26, the jagunços violently attacked four times. On the

27th, eighteen times. The next day, they didn’t respond to morning and

afternoon bombings, but attacked from six o’clock in the evening until five the

next morning.

24th Infantry

Battalion. Commanded by major Henrique José de Magalhães, this battalion was

originally from Rio de Janeiro. Reached the combat zone on August 15 with 27

officers and 398 enlisted personnel. Participated in the assault on the citadel

of Canudos on the first day of October manning the front trench, line the rear

of the command and general hospital. Photo by Flávio de Barros after the end of

fighting, against the backdrop of the ruins of the old church –

http://www.scielo.br

On October 1,

1897, an intensive bombing of the last hotbed of resistance began. A decisively

cleaned-up terrain was needed for the assault. The assault had to happen at in

a single strike, at the charge, with only one concern, the ruins.

No projectile

was wasted. The last bit of Canudos was inexorably turned inside out, house by

house, from one end to the other. Everything was completely devastated by the

heavy artillery fire. The last jagunços suffered the ceaseless

bombardment in all its destructive violence.

But no one was

seen fleeing; there wasn’t the least agitation.

And when the

final strike was shot, the inexplicable quiet of the destroyed countryside

could have made one think that it was deserted, as if the population had

miraculously escaped during the night.

The attack

began. The battalions took off from three points to converge at the new church.

They didn’t get far. The jagunços followed their attackers step by

step and suddenly came back to life in a surprising and victorious way like

always.

Corpses in the

ruins of Canudos. Photo of Flávio de Barros – www.scielo.br

All the

pre-established tactical movements were changed, and instead of converging on

the church, the brigades were stopped, fragmented and dispersed among the

ruins. The sertanejos remained invisible. Not a single one appeared

or tried to pass through the plaza.

This failure

resembled a rout, since the attackers were stopped and found themselves facing

unexpected resistance. They took shelter in the trenches and finally got out of

the fix by limiting themselves to a merely defensive strategy. Then the jagunços came

out of the smoking huts and unleashed an attack in their turn, swooping down on

the soldiers.

There was an

urgent need to expand the original attack. Ninety dynamite bombs were launched

against those who remained in Canudos. The vibrations produced fissures that

crisscrossed over the ground like seismic waves. Walls collapsed. Many roofs

fell to pieces. A vast accumulation of black powder made the air unbreathable.

It seemed as though everything had vanished. In fact, it was the complete

dismantling of what was left of the “sacred city”.

The battalions

waited for the cyclone of flames to die down before launching the final attack.

But it wasn’t

to be. On the contrary, a sudden withdrawal took place. No one knows how, but

from the flaming ruins, gunfire poured out, and the attackers ran for shelter

on all sides, mostly withdrawing back behind their trenches.

Without trying

to hide, jumping over fires and those roofs that remained standing, the last

defenders of Canudos leapt out. They launched an assault of wild audacity,

going to kill the enemy in their trenches. These enemies felt their lack. They

lost courage. Unity of command and unity of action dissolved. Their losses were

now heavy.

In the

foreground, a typical house of the place. Photo Flávio de Barros –

http://www.passeiweb.com

In the end, at about two o’clock in

the afternoon, the soldiers fell back in defense, tasting defeat.

But the sertanejos’ situation

had gotten worse, since they were blockaded in such a reduced space.

Nonetheless, at dawn on October 2,

the weary “victors” saw the day emerging under a heavy burst of gunfire that

seemed like a challenge.

In the course of the day, taking

advantage of a truce, three hundred people asked to surrender, but much to the

chagrin of the military authorities they were just exhausted women, very young

or wounded children and sick old people, all those who could no longer hold a

weapon. They were slaughtered the following night (“And words being what they

are, what comment should we make on the fact that, from the morning of the

third on, nothing more was to be seen of the able-bodied prisoners who had been

rounded up the day before…”[38]).

To tell the truth, there were no

prisoners. All the wounded jagunços who fell into the soldiers’

clutches were finished off a bit later with cold steel.

“There is no need of relating what

happened on October 3 and 4. From day to day the struggle had been losing its

military character, and it ended by degenerating completely…. One thing only

they knew, and that was that the jagunços would not be able to hold

out for many hours. Some soldiers had gone up to the edge of the enemy’s last

stronghold and there had taken in the situation at a glance. It was incredible.

In as quadrangle trench of a little more than a yard in depth, alongside the

new church, a score of fighting men, weak from hunger and frightful to behold,

were preparing themselves for a dreadful form of suicide… a dozen dying men,

their fingers clenched on the trigger for one last time, were destined to fight

an army.

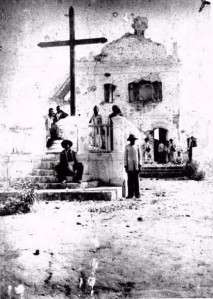

Ruins of the

Old Church of St. Anthony – http://osertanejosdecanudos.blogspot.com.br

“And fight

they did, with the advantage relatively on their side still. At least they

succeed in halting their adversaries. Any of the latter who came too near

remained there to help fill that sinister trench with bloody mangled bodies…

“Let us bring

this book to a close.

“Canudos did

not surrender. The only case of its kind in history, it held out to the last

man. Conquered inch by inch, in the literal meaning of the words, it fell on

October 5, toward dusk — when its last defenders fell, dying, every man of

them. There were only four of them left: an old man, two other full-grown men,

and a child, facing a furiously raging army of five thousand soldiers…

“The

settlement fell on the fifth. On the sixth they completed the work of

destroying and dismantling the houses — 5,200 of them by careful count.”[39]

The few men,

women and children prisoners – http://osertanejosdecanudos.blogspot.com.br

Once again the

law of the Republic ruled over the sertão. Thus, the heroic epic of

Canudos came to an end. An adventure full of humanity that perished in sound

and fury. Canudos, the empire of Belo Monte, was not defeated; it vanished

together with the last one killed. It was annihilated.

In those days,

in the province of Ceara, a vast, religiously inspired social reform movement

developed under the guidance of Father Cicero. This movement experienced a less

tragic end, because Father Cicero knew how to navigate his way with authority

among the political components of the region, with full respect for the state

and property, a compromise before power that assured him not only impunity, but

a position recognized and respected by all.

The young

priest Cicero Romao Batista – http://osertanejo.blogspot.com.br

This movement

was of a more priestly rather than blatantly messianic inspiration. The spirit

of Catholicism in both its political and social sense animated the movement

more than the spirit of millenarianism, which is purely social and has nothing

to do with politics. It intended to rediscover the pattern of the primitive

Church: devoting political means to a social mission.

Padre Cicero

had exceptional prestige. He was the only Brazilian messiah to belong to the

clergy. All the others were lay people who were carried into divine service by

vocation, but never took holy orders. He was sent into the hamlet of Juazeiro

in 1870, in the early days of his ministry, and traveled throughout the region

preaching. After this period of Franciscan poverty, he started to animate

social activity around Juazeiro with an ideal of peace according to which the

interests of all were supposed to prevail over particular interests, the source

of quarrels and conflicts. He had managed to convince small property owners and

peasants to stop living on their land and instead move to the village, near to

him. In the morning they went to work in the fields, and in the evening they

came back.

A traffic of

pilgrims began in Juazeiro. They came to ask the blessing and counsel of Padre

Cicero.

Continuaremos na próxima semana...

Extraído

do blog: "Tok de História" do historiógrafo e pesquisador do cangaço

Rostand Medeiros

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário