Photo from the

1920s, showing the center of Juazeiro in the state of Ceará –

http://www.cidadejua.com

In 1889, when

the Republic was proclaimed, Padre Cicero reacted in his way by carrying out

his first miracles, which consolidated his position and prestige. The

republican state didn’t dare to provoke hostilities and tolerated this movement

that criticized the bourgeois spirit without criticizing the state. Pilgrims

became increasingly numerous. Many settled in the holy city of Juazeiro where

they found protection with the “little father”. The Church was disturbed by

this and tried to put an end to the turbulence which it considered dangerous.

It ordered Padre Cicero not to say mass or preach anymore, but it could not

force him to leave Juazeiro. It was afraid that his followers would mobilize to

defend him, something that must be avoided at all costs.

Padre Cicero

had allies among local political leaders. His prestige, his influence, the

progressive electoral force he had available to him, pushed him to strengthen

his growing political authority by getting himself elected as municipal

prefect.

Here we see an

elderly priest Cicero among its followers – http://www.terra.com.br

In 1914, the

victory of enemies made his relations with the provincial government difficult.

The “little father” then called his followers to holy war against the

provincial government that represented the Antichrist. God wanted it to be

overthrown so that perfect happiness without shadow could reign on earth. These

incitements to struggle caused troops to be sent against the New Jerusalem. But

unlike the Counselor, Father Cicero enjoyed important political support in the

capital of Brazil; and besides, above all, this insurrection was limited to

political goals and didn’t have the ambition of overthrowing the constituted

order. The prophet’s followers, with federal complicity, triumphed over the

forces deployed against them and placed the provincial capital under siege,

putting the governor to flight. The victorious Padre Cicero officially became

the vice-governor of the state of Ceara.

In the picture

we see men who fought the forces of Father Cicero, against the troops of the

governor of the state of Ceará in 1914 – http://pt.wikipedia.org

In a world

shattered by the continuous warfare that raged among the great families and for

which the poor unfailingly paid the price, Father Cicero could institute a more

peaceful society, thus improving the tragic situation of those who had nothing.

He was able to do so, because he spoke in the name of the highest authority,

divine authority. In this way, he put himself above the fray, beyond the local

quarrels, the only way to be heard by all. In a world increasingly dominated by

selfish interests, only religion could unite, at least in appearance, what was

separated in deed. In sermons, Father Cicero reproached the “small” and the

“great”, because they did not live according to the divine laws of charity, mutual

aid and the forgiveness of offenses. He was thus able to put an end, at least

temporarily, to the hostilities between families, to blot out discord, to renew

alliances, to become the arbitrator of disputes, the indisputable and

undisputed master of the region, the “little father”.

His movement

had a conscious function of social reform. The followers made donations to the

messiah that served to form a common fund to provide for the needs of the sick,

widows and orphans, to buy land, to finance enterprises (Juazeiro, a small

hamlet in 1870, would become the second city of the province under the stimulus

of the prophet, with 70,000 in habitants). But it also had a guardian ship

function for the existing system: the ideal of fraternity and equality was

rigorously understood as fraternity and equality in faith and before god.

When Canudos

defended its freedom with arms in 1896–1897, some men left Juazeiro to go to

the aid of the commune of Monte-Santo, but the entire city didn’t rise up. And

yet, at that time, an insurrection in Juazeiro would have absolutely meant the

greatest danger for the Republic, which furthermore was very careful not to

challenge it. The state would have found itself forced to conduct a war on two

fronts. Considering the tremendous difficulty that it encountered in getting

the best of the rebels of Canudos, one could legitimately ask what it would

have been able to do in the face of an insurrection of the entire northeast, a

thing that would certainly have happened if the movement in Juazeiro had

committed itself to that struggle.

In the final

analysis, in a period disturbed by increasingly bitter rivalry between

particular interests, Father Cicero brought social peace. This allowed the poor

of the region, along with those who came from the coast, to breathe, to relax

and to rediscover with him, if not the hope of a new life, at least that of a

better life.

1934 – Funeral

of Father Cícero – http://oberronet.blogspot.com.br

After his

death in 1934, various messianic movements developed in the sertão. Most

of them were immediately stopped by the action of the local authorities, unless

they learned to follow the example of Father Cicero and come to terms with the

politicians of the region. This was the case of Pedro Batista de Silva’s

movement in Bahia. He succeeded in making the Santa Brígida precinct, where he

established his messianic community and over which he ruled with uncontested

authority, rise in the ranks of city hall.

This was not

the case of the blessed Lourenço’s movement, which lasted from 1934 to 1938 and

ended tragically.

In the image

of the “warrior saint” Antonio Conselheiro, the blessed Lourenço founded a

colony similar to Canudos in the plain of Araripe, also fully within the sertão.

Here again, the poor who no longer wanted to submit to being slaves occupied

the land, establishing a kind of primitive communism, a phalanstery. Everything

produced was held in common. This scandalous practice that openly challenged

the big property owners by violating or, worse, ignoring the laws of private

property (sacred laws that established the social authority of the possessors)

would rouse the almost immediate reaction of the united forces of the

constituted order. Thesertanejos took up arms, scythes against cannons as

in Canudos, resisting to the death. They were all slaughtered after a fierce

and relentless battle, but it was too unequal. After a short time, the law of

the Republic again ruled over the sertão.

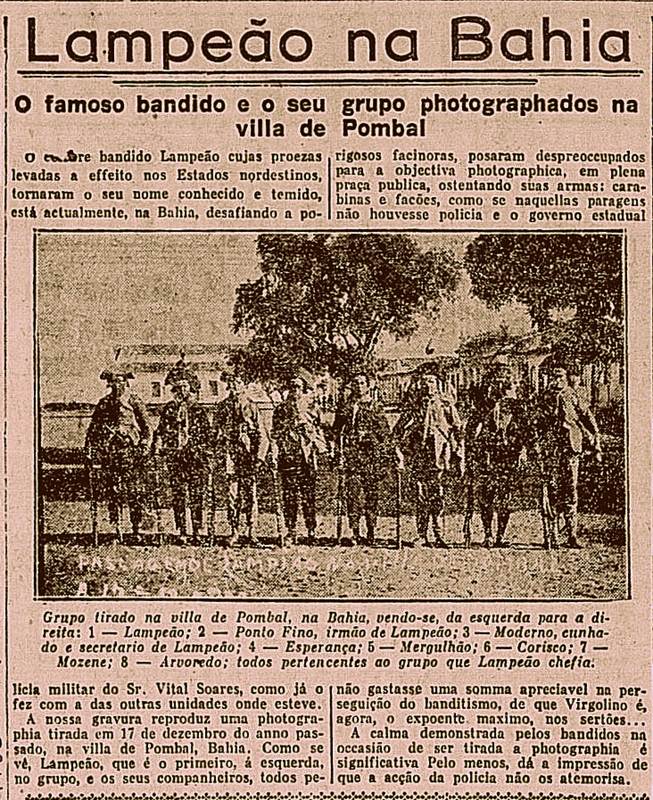

Virgulino

Ferreira da Silva, the “Lampião”, the most important bandit of Brazil –

http://blogdomendesemendes.blogspot.com.br/

In 1938, the

blessed Lourenço’s movement ended in a bloodbath. It was the last revolutionary

messianic movement. On July 28 of the same year, Lampião was killed with

some compadres at Angico. His death would be the death-blow inflicted

on cangaceirismo. The police would easily manage to get the better of the

last scattered, unsettled little groups that lacked protection or complicity.

The slaughter would be brutal.

The cangaceiro was

the social bandit of the northeast of Brazil and the cangaço was his

band. The cangaceiro avenged himself for a humiliation, an injustice,

for the blackmail imposed by a “colonel” or the police, for the murder of a

relative. He then decided to exclude himself from society and go into hiding by

uniting with an already existing band, a band that would allow him to survive

through organized theft and escape the police forces that were hunting for him.

An avenger

more than a righter of wrongs, the cangaceiro embodied generalized

rebellion against the whole social order.

Drawing a

typical cangaceiro and his characteristic outfit –

http://www.eunapolis.ifba.edu.br

The cangaceiro bands

that traveled around the northeast at the end of the 19th and the

beginning of the 20th century stood side by side with the millenarian

movements. In both equally, we find the same contempt for property and thus for

the law, the same taste for wealth, the same generosity, the same challenge

launched against the state and its cops, the same fierce determination, the

same fighting spirit, the same fury. The boundary between the two was faint

when not non-existent, and the passage in either direction was easy. We know of

famous bandits, seduced by the prophecies of the Conselheiro, who participated

in the founding of Canudos or rushed to defend it, bringing their skills and

experience. Lampião thought so highly of Father Cicero’s movement that he

always avoided the province of Ceará in the course of the raids.

In both cases,

the same people were involved.

“From a very

early age,” the university student Euclydes da Cunha wrote, “the inhabitant of

the sertão regarded life from his turbulent viewpoint and understood

that he was destined for a struggle without respite that urgently demanded the

convergence of all his energies… always ready for a conflict where he wouldn’t

be victorious, but he wouldn’t be conquered.” It probably wasn’t the nature of

the northeast that molded the fierce character of these people; but they were

truly indomitable people who preferred death to slavery. They were always quick

to defend their freedom, the idea they had of man, a certain vision of wealth,

with the greatest vigor and boldness. They stood against the entire world; and

from all sides, they were destined to a struggle without respite that urgently

demanded the convergence of all their energies, to a war in which they would

not allow themselves to be conquered.

Cangaceiros –

http://www.grupoimagem.org.br

Millenarians

or cangaceiros, they were cowhands, sharecroppers, mule drivers. They were

part of the rural society that was continually threatened in its existence and

substantially in its freedom. They had been produced by it. They not only found

a real complicity in this society, but they also expressed its deepest aspirations.

All in all,

very little differentiates the two groups. The millenarians were carriers of a

positive social project, but it had a religious essence, while the cangaceiros were

carriers of a purely negative social project that was not religious in its

essence.

United around

a prophet through faith in the imminent arrival of the Millennium, through the

same aspiration for a new life, the Brazilian millenarians formed a spiritual

community that intended to organize itself in expectation of the final event,

preparing for it. This messianic community did not have the ambition of

realizing the Millennium itself, but it did already oppose the spirit of the

existing world in a radical way by recognizing itself in the community of a

future world. It carried within itself a positive social project that

essentially remained religious; it formed the idea of a society not yet

realized and whose realization did not belong to it. It was the premonition of

this new society.

Extraído do blog: "Tok de

História" do historiógrafo e pesquisador do cangaço Rostand Medeiros

http://tokdehistoria.wordpress.com/2012/09/22/cangaco-millenarian-rebels-prophets-and-outlaws/